Eugenics and the true history of the Abortion Campaign (1)

By Ann Farmer | 15 January 2025

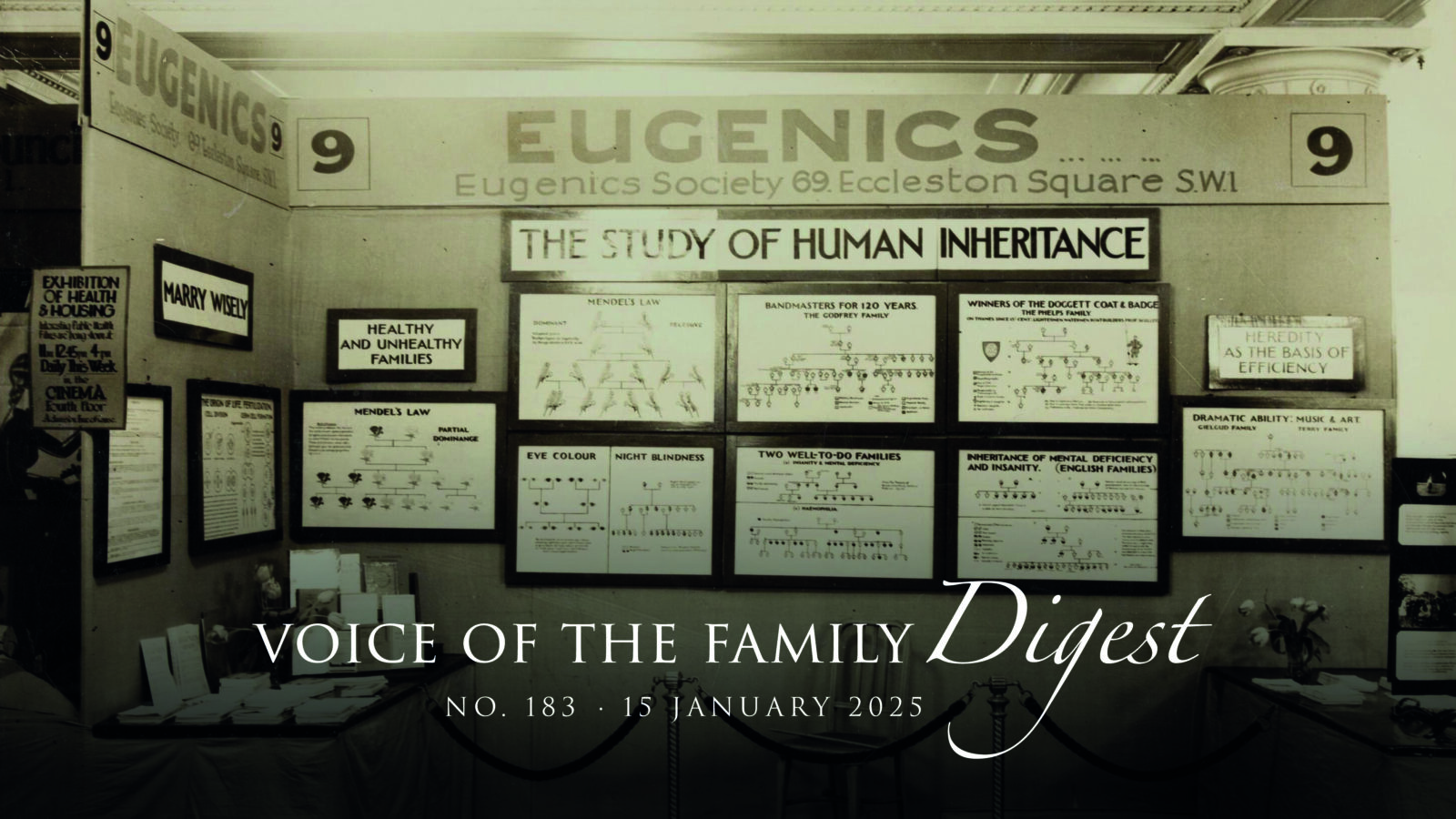

My book, By Their Fruits: Eugenics, Population Control, and the Abortion Campaign, highlights the problem that what most people know about abortion history is the “tip of the iceberg” — and it’s the wrong iceberg. Contemporaneous reports, and the Abortion Law Reform Association’s own records (tellingly, housed in the archives of the Eugenics Society) reveal the true story; but the version handed down is written by the same lobby, or rather it has rewritten the campaign’s history. Campaigners are shown as feminist and radical, and their opponents as largely male, conservative and Catholic,e.g. Dr Halliday Sutherland, dismissed as a “Catholic doctor”,1 who accused contraceptive campaigner Marie Stopes of experimenting on the poor of London’s East End; she sued him for defamation, but although eventually she lost,2 the eugenics campaign prevailed in the end.

Stopes, a doctor of palaeontology, was a eugenicist,3 and although this need not mean that illegal abortion was not a problem, the campaigners’ documented worldviews and associations highlight their true allegiance to eugenics population control — an allegiance pre-dating their abortion advocacy.

Stopes demanded, “Are these puny-faced, gaunt, blotchy, ill-balanced, feeble, ungainly, withered children the young of an Imperial race? … Mrs Jones is destroying the race!”4

Eugenicists wanted not only “unfit” individuals sterilised but their whole families, and abortion campaign pioneer Dorothy Thurtle — a prominent member of both the Eugenics Society and the Abortion Law Reform Association (ALRA),5 lent her support to the Brock Committee on Sterilisation,6 dismissed fears that sterilising “unfit” couples would prevent the births of those who “may escape the taint of physical and mental defects”, arguing that the “price of securing an unknown and doubtful number of healthy children from such unions would be a number of unhealthy children, who might pass on their defective inheritance to an unknown and increasing number of children in succeeding generations.”7

The eugenics movement was inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which posited that humankind had developed from primitive origins; they believed the proliferation of “lesser evolved” humans, encouraged by well-meaning charity and social reformers, threatened the degeneration of humanity as the worst of humans “outbred” the best.8

The Eugenics Society wanted abortion based on the Brock Committee’s report on sterilisation, which recommended that “the right to sterilization should be extended to all persons whose family history gives reasonable ground for believing that they may transmit mental disorder or defect.” They reckoned this would affect 3.5 million people but felt it “idle to expect of this group, most of whom are of subnormal mentality, a proper sense of social responsibility. But we believe that many of them would be glad to be relieved of the dread of repeated pregnancies and to escape the recurring burden of parenthood, for which they are so manifestly unfitted.”9 Sir Arnold Wilson of the Abortion Law Reform Association wanted abortion allowed only in “dysgenic” cases, after assessing the mother, and possibly, the father.10

ALRA’s legal counsel Gerald Thesiger, representing the Association at the Birkett Enquiry into illegal abortion,11 said he did “not believe” that “if you could strictly enforce the present law”, any children saved were “really worth having. They are so few in number, and I would say so likely to be bad in quality.”12 In their evidence, ALRA’s cases of mental and physical disability included a woman who “was quite unable to cope with birth control technique” owing “to her subnormal mental condition”. Eugenicists wanted abortion for sick, poor and malnourished women, and those with sick and unemployed husbands — indeed, to the eugenicist, pregnancy in any poor woman was evidence of mental deficiency.13 Alice Jenkins, co-founder of ALRA, later recalled with pleasure their inaugural meeting on the anniversary of Sir Francis Galton, founder of the Eugenics Society.14

However, ALRA’s 1936 Conference demanded “abortion for all” because advocates privately admitted that focusing on the “unfit” would suggest that they were targeting the poor — which indeed they were.15 Instead they claimed that illegal abortion, a deadly danger, was widespread among impoverished women;16 the size of poor families challenged such claims, but Dorothy Thurtle maintained that without illegal abortion, they would be even larger.17 ALRA’s vice-chairman, the Canadian Stella Browne, said poor women would not seek legal abortion “at first”, being too busy “simply … looking after the house, generally under very bad conditions”, but in time, they would “take advantage of it with gratitude”.18

The abortion campaign was a eugenics campaign: from the very beginning, in 1936, ALRA sought Eugenics Society guidance, welcoming financial and other support in a close and enduring relationship.19 They were also influenced by eighteenth-century Parson Thomas Malthus, who claimed that only famine, disease and war prevented the world from becoming grossly overpopulated. He recommended sexual restraint,20 but in the late nineteenth century, the Neo-Malthusians, his atheistic disciples, promoted contraception.21 Campaigners, rather than sympathising with women killed by illegal abortion, sympathised with those unable to obtain abortions: Sir Arnold Wilson, Conservative MP and ALRA member, said he had “less concern with those who die as a result of dangerous [abortion] methods than with those who live unfit, frustrated lives”. Alice Jenkins echoed eminent physician and ALRA patron Lord Horder in saying she was “not so much concerned about those who do obtain abortion, but with those on whom an operation ought to be performed, but who because of the diffidence, sense of risk, and avoidance of trouble on the part of their own medical practitioner, are left to their fate”.22

But among themselves, campaigners admitted that it was wealthy women who sought abortions: Dr Joan Malleson, an adviser to ALRA,23 complained to ALRA co-founder Janet Chance that, in her private medical practice, it was “common to get people whose reasons are entirely ‘frivolous’ from the legal point of view. Last week I had a woman who had had six abortions — a society lady — and she thought because she was tired she could have another free ‘because they are so expensive’!!” Malleson feared the effects on the medical profession: “Every doctor will know cases such as this, and I think you should always bear them in mind because they naturally make a lot of opposition in medical circles to making abortion cheap, and free and easy!”24

Malleson also knew that women changed their minds: “I see so many women, and my impression is that there is an extraordinary widespread instability in early pregnancy.” Stella Browne agreed; she also acknowledged “abortion regret”: “[U]nfortunately many women in the pregnant state are unstable in wishes and will, and there have been cases where humane and kindly doctors have met the woman’s frantic wish and have operated, and then had the experience of being told, ‘Oh why didn’t you leave me alone?’” Browne suggested a waiting period of two or three weeks, believing “many women in the early stages of pregnancy are unreliable to a very high degree” — but believed female “instability” should “never be made an excuse for definite refusal to operate.” ALRA member Mrs Selwyn Clarke said there “may be a number of women, probably mainly middle class, who do have fancies and emotional reactions”, but claimed that the “working class woman” with many children should have the right to abortion because of her “lack of vitality and energy”, insisting: “[A]s serious minded people … we should stick to our main purpose, and if here and there a woman changes her mind, do let us realise that it is not very important.”25 Clearly, campaigners’ first priority was not women’s welfare, or even women’s choice.

Illegal abortion methods included potions purporting to deal with “female ailments” and “obstructions”, but if powerful enough to kill the baby they could also kill the mother. With no pregnancy tests, it was impossible to prove these potions “worked”, and the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act outlawed the procurement of “miscarriage” via drugs or instruments, regardless of whether the woman was found to be pregnant. Interference with instruments, before the advent of antibiotics and blood transfusions, risked horrendous physical damage, blood poisoning and death. Before the arrival of the curettage operation in the late nineeenth century (which could also be used for therapeutic purposes) the age-old way of killing an unborn child was to beat the mother, but this risked killing the mother as well — a crime harder to conceal.26

Medical authorities disputed claims that death certificates were sometimes falsified to conceal abortion fatalities, and although campaigners wanted abortion legalised for mothers-of-four allegedly to save lives,27 the first birth was always the most dangerous, and statistics showed that wealthier mothers, with fewer children, were at greater risk. If abortion was a factor, it affected a different class altogether.28 Claims about widespread illegal abortion were also challenged by the illegitimacy figures, and although most poor unwed mothers did subsequently marry,29 unsupported pregnant mothers sought refuge in mother and baby homes run by Christian charities, or the parish workhouse where, as noted by suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (not an abortion advocate), they had to choose between earning their keep by manual labour in the workhouse, separated from their child, or leaving, destitute, with a two-week-old baby. Only too often, they turned to prostitution.30

As in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, the workhouses were deliberately grim, to deter those not in absolute poverty. And yet they were never empty, and were still operating in the 1920s and 30s, when my own father experienced the stigma of being a “workhouse boy” after his father deserted the family; his little sister died there, and he vividly recalled he and his brothers being separated from their mother and sisters at the workhouse door, when, in line with Malthusian thinking, families were segregated along the lines of sex to prevent the poor from breeding.

Regarding backstreet abortion, ALRA’s first conference opposed stiffer penalties for offenders;31 executive member Beryl Henderson even called for the “liberation” of illegal abortionists from prison, in order to benefit from their “expert knowledge and experience”.32 In 1934, the left-wing Women’s Co-operative Guild, in which Stella Browne33 was active, called for an amnesty for jailed women abortionists.34 Campaigners failed to condemn backstreet abortion per se, and while graphically describing the dangers, refrained from condemning those responsible. The Birkett Enquiry found “relatively few cases” involving a “sympathetic friend or neighbour”,35 and abortionists, some of whom worked in criminal circles,36 included males who charged for their “services”;37 the image of the poor woman helping friends and neighbours was largely the work of abortion advocates like Stella Browne.38

ALRA’s Gerald Thesiger, making similar claims to the Birkett Enquiry, was challenged by one Committee member, who referred to his claim that the police were “inclined to state in conversation that they ‘had to prosecute’ but the accused had done ‘quite a lot of good’”; Captain M P Pugh said: “I have talked to hundreds of policemen who have been in these cases, and I have never once heard one of them make a statement anything like that.” Thesiger hastily revised his claims, while revealing his own eugenics sympathies: “Those who have seen the quasi-mental defects, who may have proceeded [sic] the accused person in the dock, can appreciate the sentiment. The sympathy of the crowd is strongly with the accused.”39

Eugenicists believed that abortion improved the race by eliminating “quasi-mental defects” before birth, and wanted it legalised with the same aim; but police witnesses to the Birkett Enquiry took a sterner view: Metropolitan Police Chief Constable, J E Horwell considered the law a deterrent against backstreet abortion and recommended even stiffer penalties, describing a notorious female backstreet abortionist who, he believed, got off too lightly after pleading guilty to manslaughter, as “a very old and dirty woman”; she was sentenced to eighteen months in prison.40

This series will continue next month with Eugenics and the true history of the Abortion Campaign (2).

Notes

- https://hallidaysutherland.com/2023/04/02/the-b-b-c-s-fight-against-disinformation/ ↩︎

- Sutherland, M., Exterminating Poverty: The true story of the eugenic plan to get rid of the poor, and the Scottish doctor who fought against it (n.p., 2020). ↩︎

- See: Hall, R., Marie Stopes: A biography (London: Andre Deutsch, 1977); Rose, J., Marie Stopes and the Sexual Revolution (London: Faber & Faber, 1992). ↩︎

- “Mrs Jones Does Her Worst”, Daily Mail, 1919, in Trombley, S., The Right to Reproduce: A History of Coercive Sterilization (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1988), p 79. ↩︎

- Farmer, A. E., By Their Fruits Eugenics, Population Control, and the Abortion Campaign (CUA Press, 2008), numerous references. ↩︎

- A committee set up with the approval of the Minister of Health, in June 1932, charged with making recommendations on the sterilisation of the “feeble‐minded” in England and Wales, and specifically, “To examine and report on the information already available regarding the hereditary transmission and other causes of mental disorder and deficiency; to consider the value of sterilisation as a preventive measure having regard to its physical, psychological and social effects and to the experience of legislation in other countries permitting it; and to suggest what further enquiries might usefully be undertaken in this connection.” It was presented by the Minister of Health to Parliament in December 1933. ↩︎

- Birkett Enquiry Minority Report, in Dickens, B. M., Abortion and the Law (Bristol: Macgibbon & Kee Ltd., 1966), p 135. ↩︎

- See: Chesterton, G. K., Eugenics and Other Evils (London: Cassell & Company Ltd., 1922); Kevles, D. J., In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Harvard University Press, 1985); McLaren, A., Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada 1885-1945 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Inc., 1990); Kühl, S., The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Soloway, R., Demography and Degeneration: Eugenics and the Declining Birthrate in Twentieth-Century Britain (Chapel Hill/London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Pernick, M. S., The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of ‘Defective’ Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures Since 1915 (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); Stone, D., Breeding Superman: Nietzsche, Race and Eugenics in Edwardian and Interwar Britain (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002); Black, E., War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press. 2004); Broberg, G., Roll-Hansen, N. (Eds.), Eugenics and the Welfare State: Sterilization Policy in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2005); Weikart, R., From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany (Houndmills, Hants.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). ↩︎

- Brock Report, in Trombley, S, The Right to Reproduce: A History of Coercive Sterilization (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988), p 125. ↩︎

- An interdepartmental Royal Committee of Enquiry into illegal abortion established by the British Government in 1937. ↩︎

- An interdepartmental Royal Committee of Enquiry into illegal abortion established by the British Government in 1937. ↩︎

- ALRA, evidence to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry), 13 October 1937 (MH71-21 AC Paper 25). ↩︎

- “Cases which illustrate the difficulties of obtaining therapeutic abortions owing to the ambiguity of the law” (Appendix to ALRA memorandum to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-21 AC Paper 25). ↩︎

- Jenkins, A., Law for the Rich (London: Charles Skilton Ltd., 1964), p 49. ↩︎

- Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/D1 ↩︎

- Birkett Enquiry member Sir Comyns Berkeley precipitated a difficult situation when he questioned a fellow Committee member, ALRA member Dorothy Thurtle, on her knowledge of backstreet abortion, “Mrs Thurtle said a short while ago that she knew of a place where this was done without any secrecy at all. Could she give us the name if there is no secrecy?” Thurtle responded, “Did I say that?” Berkeley persisted, “Yes; and I am rather inquisitive about it.” Thurtle was saved from further difficulties when the Chairman, Sir Norman Birkett, himself sympathetic to abortion reform, reminded Committee members that “questions had better be directed to the witnesses” — Medical Women’s Federation, Evidence to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry (MH71-25, AC Paper 123). On another occasion, Thurtle claimed that when a young woman got married, went into a couple of rooms, and had half a dozen children, she “just lets everything go. She just cannot keep up with anything, and she just does not bother”; her implied admission that poor women with large families did not seek abortion was a dramatic reversal of earlier claims. — London County Council, Evidence to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-26 AC Paper 132). ↩︎

- Chairman of the inquiry Sir Norman Birkett expressed surprise at evidence revealing that illegal abortions involved so few mothers of large families: “That was totally contrary to what one had always been led to expect” — Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry), 13 April 1938 (MH71-26 AC Paper 132). See: Soloway, R., Birth Control and the Population Question in England 1877-1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982). ↩︎

- Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-23 AC Paper 51). ↩︎

- Letter, Alice Jenkins to C. P. Blacker, March 2, 1936 (Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/C192). ↩︎

- Malthus, T. R., An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798). Malthus, who was inspired by a talk given in London by Benjamin Franklin, believed that population multiplied in geometric progression (2, 4, 8, 16, etc.) while resources grew by arithmetic progression (2, 4, 6, 8, etc.), consequently there would never be sufficient food for the population, whose growth could only be restricted by war, disease, hunger, etc. Indeed, in the face of health improvements brought by the Industrial Revolution, which to him presaged overpopulation and hunger, Malthus proposed avoiding the inevitable famine deaths by doing the very opposite of what most people regarded as progress: “[W]e should sedulously encourage the other forms of destruction, which we compel nature to use. Instead of recommending cleanliness to the poor, we should encourage contrary habits. In our towns we should make the streets narrower, crowd more people into the houses, and court the return of the plague. In the country, we should build our villages near stagnant pools, and particularly encourage settlements in all marshy and unwholesome situations. But above all, we should reprobate [i.e. reject] specific remedies for ravaging diseases; and restrain those benevolent, but much mistaken, men who have thought they were doing a service to mankind by projecting schemes for the total extirpation of particular disorders” (Chase, A., The Legacy of Malthus: The Social Costs of the New Scientific Racism (New York: Knopf, 1977), p. 7, in Mosher, S. W., Population Control: Real Costs, Illusory Benefits (New Brunswick, N. J.: Transaction Publishers, 2009), pp 31–35). ↩︎

- See: Farmer, A. E., Prophets & Priests: The Hidden Face of the Birth Control Movement (London: St Austin Press, 2002). ALRA advertised in Malthusian League’s journal, the ironically titled New Generation, where Browne reported on the campaign’s progress;[New Generation, Vol. XVI No. 1, January 1937. even before ALRA’s formation, she sought the Eugenics Society’s advice.[Letter, C. P. Blacker to Janet Chance, 7 October 1935 (Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/C65). ↩︎

- Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/D1. ↩︎

- Jenkins, A. 1964. Law for the Rich. London: Charles Skilton, p 49. ↩︎

- Letter, Dr Joan Malleson to Janet Chance, July 31, 1951 (Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/ALR/A17/1). ↩︎

- Eugenics Society File: SA/EUG/D1. ↩︎

- See: Dellapenna, J. W., Dispelling the Myths of Abortion History (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2006). ↩︎

- Dorothy Thurtle proposed that abortion be legalised for mothers of four (by inference, the poor) claiming that the death rate rose after the fourth child; she reiterated the proposal in her Birkett Enquiry Minority Report — Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry), 6 July 1938, (MH71-27 AC Paper 152). Abortion advocate Dr Helena Wright claimed mothers of four tried to terminate every subsequent pregnancy. — Memorandum to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-25 AC Paper 126). ↩︎

- Although middle class women were fewer in number, proportionately more died of maternity causes than working class women; first births were more dangerous, and middle class women had fewer children, later in life. Thus, delaying or limiting families, as advised by birth control campaigners, and the unacknowledged problem of medical abortion, may have worsened the maternal mortality rate. — Lewis, J., The Politics of Motherhood (London: Croom Helm, 1980), pp 42-3). See: Keown, J., Abortion, doctors and the law: some aspects of the legal regulation of abortion in England from 1803 to 1982 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002). ↩︎

- The UK had a low level of illegitimacy from 1900 to 1960 compared with many European countries (Tranter, N., British Population in the Twentieth Century (Basingstoke, Hants.: Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996), p. 88).In 1938, in England and Wales, illegitimate births were 4.3% of the total, although by 1945 they had risen to a peak of 9.36% MacFarlane, A., Mugford, M., Birth Counts: Statistics of pregnancy and childbirth (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1984), pp. 141-142. Most unwed pregnant working-class women “did, of course, subsequently marry” — Roberts, E., Women and Families: an Oral History, 1940–1970 (Oxford: Blackwell Roberts, 1995), pp. 69-70. In 1964, 7.2% of children were born out of wedlock; by 1994, the figure was 42.2% (Morgan, P., Marriage-Lite: The Rise of Cohabitation and its Consequences (London: Civitas, 2000), p 21). ↩︎

- Pankhurst, E., My own story (London: Virago Ltd, 1914/1979), pp. 27-28. ↩︎

- Jenkins, A., Law for the Rich (London: Charles Skilton Ltd., 1964), p 94. ↩︎

- Memorandum to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-22 AC Paper 52). ↩︎

- Vice-chairman of the Abortion Law Reform Association (ALRA), at its official inauguration on 17 February 1936 (Farmer, A. E., By Their Fruits Eugenics, Population Control, and the Abortion Campaign [CUA Press, 2008], p 14. ↩︎

- Rowbotham, S., A New World for Women: Stella Browne – Socialist Feminist (London: Pluto Press, 1977), p 35. ↩︎

- Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry), 1939, p 119. Campaigners’ references to “unskilled” abortionists implied that some were skilled. ↩︎

- Earlier criminal cases show that extra-marital pregnancy was often at the root of murder; for cases of pregnant young women murdered by their lovers in mid-Victorian Essex, see: Gray, A., Crime and Criminals in Victorian Essex (Newbury, Berks.: Countryside Books, 1988), pp 26–32. ↩︎

- Parry, L. A., Criminal Abortion (London: John Bale, Sons & Danielsson Ltd., 1932), p. 51; p. 55; p. 61; p. 65; p. 67; p. 79; a clergyman, the Rev. Francis Bacon, was involved in dealing in abortifacients, as were the Chrimes brothers in the late nineteenth century (Ibid, p 146; p 152). ↩︎

- “[T]here are cases of women who, whether with some midwifery training or a natural turn for practical medicine, have come to the aid of their friends and neighbours in this way, almost habitually, and earned thanks and blessings instead of bringing disaster (Browne, F. W. S., “The Right to Abortion”, in Browne, F. W. S., Ludovici, A. M., Roberts, H. (Eds.), Abortion (3 Essays), (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1935), pp. 29–34, quoted in Bland, L., Doan, L. (Eds.) Sexology Uncensored: The Documents of Sexual Science (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998), pp. 155–158. The only instance in which campaigners acknowledged the self-help/mutual help characteristic of poor communities was in relation to illegal abortion. ↩︎

- Memorandum to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry) (MH71-18 AC Paper 13). ↩︎

- Evidence to Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion (Birkett Enquiry), January 26, 1938 (MH71-24 AC Paper 89). ↩︎