Put not your trust in princes

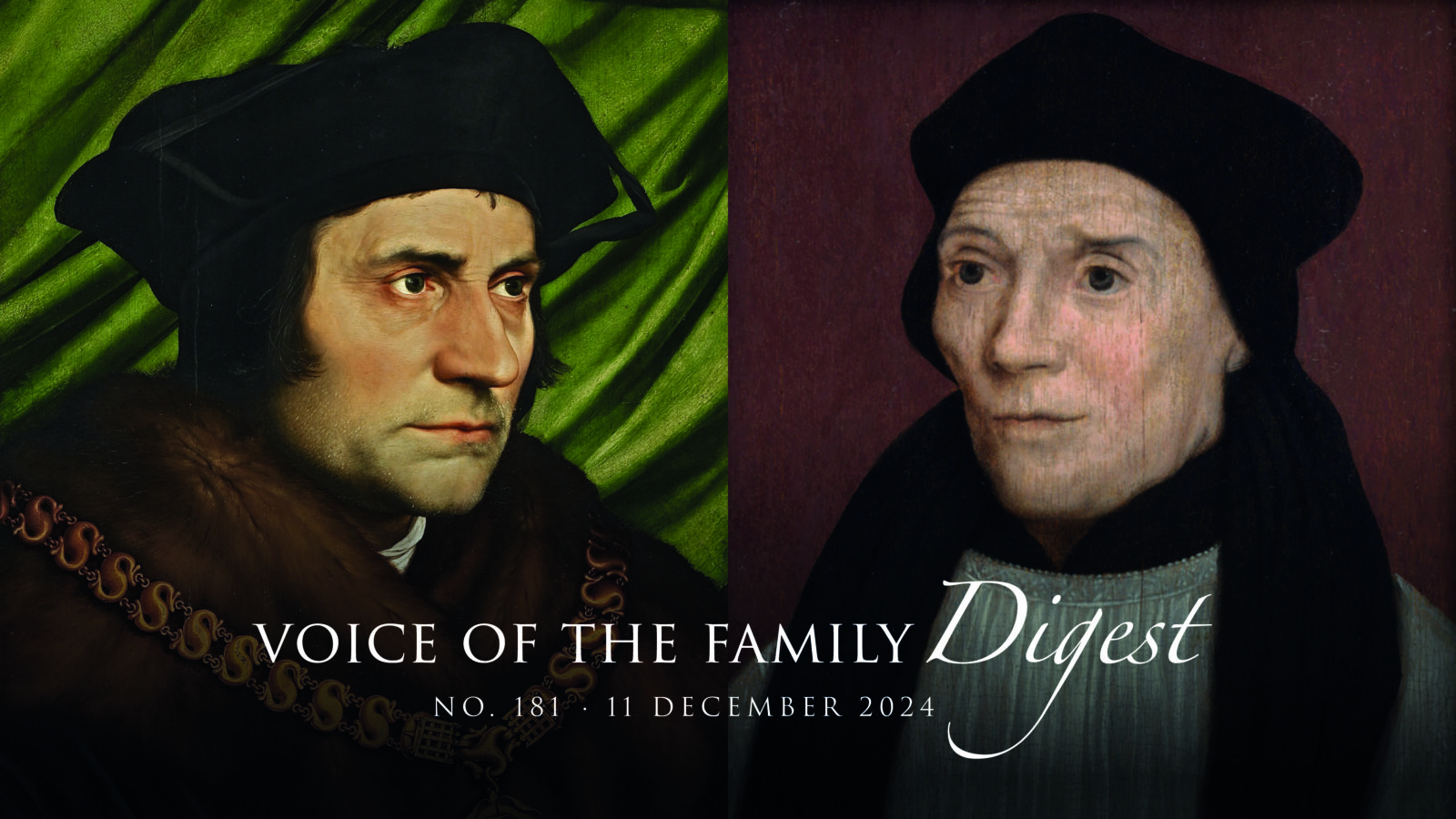

By Alan Fimister | 11 December 2024

“Put not your trust in princes: in the children of men, in whom there is no salvation” (Ps 146:3)

As we survey the prospects for the pro-life movement and for the advancement of the Gospel in the coming year 2025, it can be tempting to imagine that there is more hope in the temporal than in the spiritual order. For all his undoubted shortcomings, the re-election of the forty-fifth president of the United States as its forty-seventh president is certainly felt as a setback by the propagators of the culture of death. The ecclesiastical landscape on the other hand is mired in doctrinal confusion and disciplinary anarchy and collapse.

The Dominican prophet and reformer Girolamo Savonarola is often mistakenly described as “apocalyptic”. In fact, while Savonarola certainly thought the landscape of civil and ecclesiastical corruption that surrounded him sufficiently bleak to constitute the final apostasy, he also noted that many of the necessary precursors of the end times were not fulfilled and were unlikely to be in the near future. His conclusion was that a great renewal of the Church was only a few decades away, although not before Rome would suffer a terrible chastisement. Both these expectations were fulfilled in the sack of Rome in 1527 and the Tridentine reform thereafter.

Just a few years after Savonarola’s judicial murder by Pope Alexander VI, another great reformer, St John Fisher, was appointed Bishop of Rochester. Rochester was the poorest See in England but Fisher, faithful to the discipline of Nicaea, spurned ecclesiastical ambition and always refused translation to another diocese. Like Savonarola, he was grimly aware of the scale of ecclesiastical corruption which faced the Church. He conceded that his opponents, the Lutherans, were not wrong to think of the Roman curia that:

“Nowhere else is the life of Christians more contrary to Christ than in Rome, and that, too, even among the prelates of the Church, whose conversation is diametrically opposed to the life of Christ. Christ lived in poverty; they fly from poverty so far that their only study is to keep up riches. Christ shunned the glory of this world; they will do and suffer everything for glory. Christ afflicted himself by frequent fasts and continual prayers; they neither fast nor pray, but give themselves up to luxury and lust. They are the greatest scandal to all who live sincere Christian lives, since their morals are so contrary to the doctrine of Christ, that through them the name of Christ is blasphemed throughout the world.”

Just a year before St John Fisher was consecrated Bishop of Rochester, Savonarola’s murderer, Alexander VI, the most scandalous pope since the eleventh century, went to his eternal reward. While none of the pontiffs who followed Alexander VI in the sixteenth century were as spectacular in their vices as the 213th successor of St Peter, it would still be three decades before a Pope was elected who would seriously attend to the problems facing the church, and more than four decades until the opening session of the Council of Trent.

Just five years after Fisher took possession of his see, Henry VIII succeeded to the English throne, ushering in, or so it seemed, a new golden age for England. St Thomas More greeted the coronation with euphoria:

“This day is the end of our slavery, the beginning of

our freedom, the end of sadness, the source of joy,

for this day consecrates a young man who is the everlasting

glory of our time and makes him your king—

a king who is worthy not merely to govern a single

people but singly to rule the whole world—

such a king as will wipe the tears from every eye

and put joy in the place of our long distress.”

If the papacy was not the source of renewal for the Church of that age, perhaps this new monarch could be? Henry VIII, ally of the Habsburgs, defender of the Holy See, who declared he married Queen Catherine of Aragon for love, and would be proclaimed Fidei Defensor by the Pope and Rex Thomisticus by Martin Luther (he didn’t mean it as a compliment) would of course prove one of the bloodiest persecutors of the Church in a thousand years. Along with his and Catherine’s nuptials, one of the signs that Henry VIII’s reign would be a new golden age was his immediate arrest and imprisonment of his father’s ruthless tax gatherers Empson and Dudley. Too few noted at the time that the charges of treason on which they were tried and executed were obviously nonsense and that these men had been judicially murdered no less than the Italian friar a decade earlier. It would take a few more years of sober reflection on the king’s character for More to realise that “if my head should win him a castle in France it would not fail to go”.

Henry VIII was probably the most educated man ever to sit upon the throne of England. The assumption that his Assertio Septem Sacramentorum was ghostwritten for him ignores this fact. This education, however, combined with the temptations and opportunities of royal power and his inborn tendencies to cruelty and lust would transform him into the monster who accomplished the spiritual ruin of his country.

Neither the papacy nor the episcopate in general were sources of renewal for the Church of that age. Though the Cardinals purportedly wear red in order to signify their willingness to die for the faith, St John Fisher (who was made a Cardinal in the Tower and may have never known of the fact) is the only member of the Sacred College ever to have died a martyr. And though England was one of the least corrupt regions of Christendom in terms of clerical conduct, every single English bishop capitulated to Henry VIII’s heretical and schismatic acts except for Fisher.

But the renewal, which did eventually forestall the temporal destruction of the Church in the face of the Protestant tsunami, nevertheless required papal backing to succeed and though the Emperor (Charles V) was far more urgent and sincere in his desire for an Ecumenical Council than any of the popes who presided during his reign (1519–1555), the sort of council he would have obtained if he had had his way would have been a catastrophic exercise in theological equivocation. The Emperor John VIII Palaeologus explained at the Council of Florence in the fifteenth century that he possessed (as the head of the laity) the right to demand that the bishops do their job and pass judgment upon a disputed question of the faith whose obscurity is harmful to the people, but he could not usurp from the bishops the right of actually making that judgment.

Many of the “movements” and new orders that have grown up in the decades since the council in order to circumvent poor or malign episcopal government have proven blind alleys. Sometimes the “founder” proves to have been a fraud and a predator; sometimes the movement turns out to be a cover for some absurd private “revelation”. The problem is that monarchical episcopacy was instituted by Christ for the duration of time as the proper structure for the government of His Church, and so episcopal corruption cannot be circumvented — it must be dealt with. More and Fisher pursued their own duties, according to their states in life, with their eyes open to the reality of the world around them. Renewal came but it took their sacrifice to bring it about.

When Moses called upon the people of Israel to appoint elders to assist him in the government of the nation (Dt 1:13), the spirit descended upon the seventy who were chosen, but also upon another two who had not been selected. Joshua protested and called upon Moses to silence them. Moses rebuked him, “are you jealous for my sake? Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets!” (Nm 11:29). But when Korah and his followers sought to rebel against the government of Moses, the ground opened up and swallowed them alive and those who were dismayed were struck down with plague.

Today many Catholics are, like St John Fisher, dismayed at ecclesiastical developments and find themselves distrustful of the government exercised by the wielders of spiritual power. The faithful of this time are also, like St Thomas More in 1509, inclined to rejoice at the turn taken by political events and to look to that quarter for some sort of improvement in the monstrous state of things. Like Eldad and Medad, who prophesied in the camp, St Thomas More and St John Fisher were not mainstream figures in their own day but critics of the shortcomings of ecclesiastical and civil culture. Nevertheless, they would remain loyal to legitimate authority for all its shortcomings and even when that loyalty was punishable by death.

It is an ancient saying among Catholics that Christians are not so much called to be Christians as to be alter Christus — ipse Christus. The word Christ means “the anointed one”. Jesus is anointed by virtue of His Godhead with the Holy Spirit. The prophets, priests and kings of the Old Testament were anointed with oil to signify the gifts of the spirit to them for their office, just as we are anointed in the sacraments and sacramentals of the New Testament. Jesus first manifested himself as the Anointed One in the Jordan when He was baptised by John and the Spirit descended upon Him in bodily form like a dove. Then He was driven by the Spirit (Mk 1:12) into the desert where the Devil sought to tempt Him. In the three temptations, the Devil tried to lead Christ astray in each of his three anointed roles in the three places proper to those roles. The desert (for prophecy), the temple (for priesthood), and finally he shows Jesus all the kingdoms of the world and their glory and offers them to Him if only He will bow down and worship him as the king of this world.

Savonarola, Fisher and More provide helpful exemplars of men who were not led astray by those temptations. Do not listen to prophets who profit from the prophecy but to the voice crying in the wilderness. Do not tempt the Lord by ignoring ecclesiastical corruption on the basis that the gates of hell cannot prevail — so why worry? Do not give in to the allure of all the kingdoms of the world if the price is the worship of the prince of this world.